This post by Bart Hekkema is part of a series on Sustainable Academia—in cooperation with Historians for Future—in which contributors reflect on the conditions of historians in Europe and beyond (especially those in early career stages), introduce visions for the field, and suggest concrete action in order to build more inclusive and supportive academic environments.

In my Twitter feed, I occasionally read posts ‘for future historians’. These might describe a remarkable event in world politics, something that will be remembered later on, or they might comment on how governments have again missed their climate- and biodiversity goals. It always gives me a feeling of unease, as if historians are only here to describe and analyse what happened, instead of also trying to change the course of history for the better.

The role of the historian

I think it is our responsibility as historians and human beings to take part in the discussion on how to resolve and avert future catastrophes. This made me think about the open letter from hundreds of historians that was published in January 2020 in response to the severe droughts, bushfires and climate change in Australia. The letter asks for action but also shines a light on how past societies have dealt with rapid climate changes and urgent calls for action. To move to a net zero emissions future will not be easy and entails huge investments and great dedication. But it is our responsibility to show how society is capable of rapid adjustments and adaptations. Historical examples range from the quick construction of railways, to electrification, sewerage and digital technologies. History offers stories that might inspire governments and people to act in countering climate change and its effects. It does not offer the solution or a roadmap for the future, but it can inspire us and guide our thinking about climate change, sustainability and historical analogies. The concluding remark of the letter: ‘our present challenges are not beyond us if we act now’, is a powerful statement.

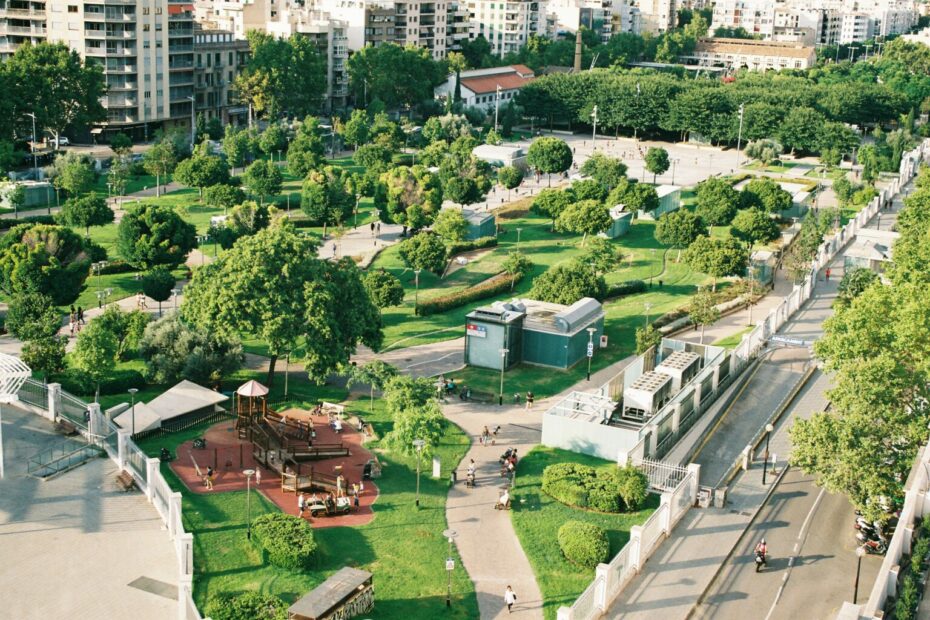

In my own recent research I have focused on how cities can take a leading role in the transition to a greener environment by rethinking urban and spatial planning. I drew on the works of Timothy Beatly and Steffen Lehmann, and believe this rethinking can be fostered by embracing the principles of Green Urbanism. This goes beyond greening the city itself, by incorporating ideas about fostering more social cohesion and wellbeing, as well as making neighbourhoods more healthy green places and mitigating the unequal distribution of services. Greening policies should in essence also be social policies. I therefore think it is important to include insights from urban planning, sociology but also history, for example by analysing past urban planning experiences and how cities have dealt with issues such as unsustainability and inequalities.I have used these insights, which I gathered from reading and researching during my studies, when I contributed to an initiative for the municipal council of the Dutch city of Groningen, in which we proposed to make green and sustainable urban design the norm for future urban planning and design. With the embracement of the proposal we hope to contribute to restoring biodiversity but also adapting to climate change and making neighborhoods greener and healthier places to stay in the foreseeable future.

Sustainability in education

A programme like the University of Groningen’s MA ‘Un/sustainable Societies: Past, Present and Future’, on which I am a student, can help us develop new perspectives on how historians might contribute to discussions about sustainability, the climate crisis and biodiversity loss, the most pressing issues of our time. Becoming aware of the entanglement of human history and nature helps going beyond the schism of nature and human affairs, a notion that has been dominant in historical thinking and writing for a long time. Critically addressing earlier histories helps to reinterpret human-nature relationships, and social and cultural values which are often rooted in unequal power relations. Personally this not only helped me in becoming more conscious but also gave me the inspiration to apply these new perspectives and insights in practice.

This type of education should not only encourage students to be curious about how we got to the verge of climate disaster and biodiversity collapse, but it can also stimulate questions that confront these realities and experiences, which differ in place and time. Historians and students of history should try to interpret, contextualise and also understand historical developments and trajectories of human affairs in relation to nature. A programme like this should be one element of our responsibility for the environmental education of coming generations, by critically engaging in debates and pointing at the historical dimensions of topical issues like unsustainability, through examples of climatic distress from droughts to resource and food shortages, as well as the impacts of colonial agricultural policies and trade systems. And not only does it help us to understand these peculiar developments and trajectories and how these reflect certain political power relations and social values, it also enables us to act upon them.

In my opinion historical knowledge can serve as a guide for policy choices and proposals for action, but it should also try to explore causalities and how alternative models for a more sustainable future in the past have been ignored or deliberately excluded from policy making and dominant cultural and political narratives. Historians therefore have a huge responsibility and task, not only now and in the future but also for the future.

Bart Hekkema is a Master’s student of History at the University of Groningen. He is following the programme ‘Un/sustainable Societies: Past, Present and Future’. Aside from his studies, he is working as a political assistant and ‘dual municipal councillor’ for the Party for the Animals in the municipal council of Groningen.